By Yankuba Jallow

The Gambia Court of Appeal in a unanimous decision held that the Janneh Commission of Inquiry recommendations cannot legally render a binding decision which may be executed or enforced as if it were a judgment or order of a Court.

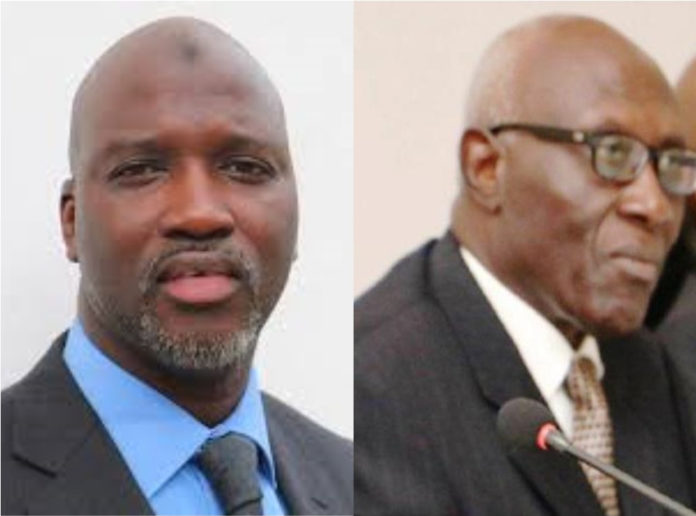

In delivering a judgment in the case of M.A Kharafi Versus The Attorney General, Justice Omar M.M Njie said: “A Commission of Inquiry does not and legally cannot make a judgment. In other words, a Commission of Inquiry cannot legally render a binding decision which may be executed or enforced as it were a judgment or order.”

Justice Njie added that “the adverse findings and recommendations of the Commission of Inquiry are merely advisory and not conclusive and binding.”

The judge said the Commission of Inquiry is part and parcel of the Executive and not part of the Judiciary, thus, not an adjudicatory body.

The appeal was filed on the 26th June 2019 by M.A. Kharafi and Sons Company Limited challenging the adverse findings of the Commission of Inquiry into the Financial Activities of Public Bodies, Enterprises and Offices as it regards their dealings with former President Yahya A.J.J. Jammeh and connected matters.

The Commission recommended that ex-President Yahya Jammeh is liable to pay $7,367,426 to the Government of The Gambia and while Kharafi should pay $2,367,426 plus interest of 5% per annum starting 30th June 2004 to 29th March 2019.

Kharafi challenged these adverse findings by the Commission before the Court of Appeal seeking a stay of execution pending the determination of the appeal.

The Court of Appeal held that a commission of inquiry is not a court and therefore, its report submitted to the Government, is neither a judgment nor an order which is capable in itself of being executed. The court relied on the Supreme Court judgment in the case of Feryale Ghanem versus the Attorney General where the Chief Justice, Hassan B. Jallow stated that a Commission of Inquiry is not a law making body, it has no legislative powers and does not fall within the legislature. Justice Njie added that Chief Justice Jallow said a commission of inquiry is an investigative fact finding body which makes findings and recommendations that are subjected to the approval of the government. Jallow detailed that while a commission of inquiry has a duty to act fairly, impartially and independently is nonetheless, not an adjudicatory body adding it is not a court of law.

Justice Njie cited section 120 (2) of the 1997 Constitution which provides “The judicial power of The Gambia is vested in the courts and shall be exercised by them according to the respective jurisdictions conferred on them by law.”

“Consequently, my view is that the adverse findings or recommendations of a Commission of Inquiry cannot be executed or enforced; they are not judgments or orders of an adjudicatory body,” he said, as he relied on section 202 (1) of the 1997 Constitution which provides that a Commission of Inquiry is set up to investigate or conduct an inquiry.

Justice Njie relied on the Indian Supreme Court decision in the case of Shri Ram Khrisna Dalmia versus Shri Justice S.R. Tendulka and Others (1959). In that case, the court held that the only power that a commission of inquiry has is to inquire and make a report and embody therein its recommendation. The Commission has no power of adjudication in the sense of passing an order which can be enforced ‘proprio vigori’.

He pointed out section 204 (2) of the 1997 Constitution which provides “A person against whom any such adverse finding has been made may appeal against such finding to the Court of Appeal as of right as if the finding were a judgment of the High Court, and on the hearing of the appeal the report shall be treated as if it were such a judgment.”

Justice Njie said clearly, from the Constitution, it is only for the purpose of an appeal that a report of a Commission of Inquiry is looked on or treated by the law as a judgment and not otherwise, certainly not for the purpose of execution.

Justice Njie maintained that the powers of a Commission as stated in the Constitution in relation to the powers of a High Court is limited to the manner or conduct in which it investigates and to makes interim orders. He relied on the Supreme Court judgment in the case of Feryale Ghanem in which the Chief Justice, Hassan B. Jallow said “a commission of inquiry is thus an instrument of good governance designed to enable the state to investigate expeditiously and effectively matters of public interest and concern and to make remedial measures for the public good. Whilst it is not a court of law, a commission should be able to exercise some of the powers of a court, if it is to discharge its mission effectively. Hence, the vesting of the powers of the high court judge at trial in the Commission in respect to matters set out in section 202 (2) of the Constitution.”

Is a White Paper a Legal Instrument?

The Court of Appeal held that a White Paper is a written announcement or statement of government policy on a particular issue of public interest.

“A White Paper certainly does not emanate from the Commission of Inquiry and it is, as a result, not part of the report of the Commission. It is not legislative character and it is certainly not a judgment or order of a court of law,” Justice Njie said.

Justice Njie said section 203 (a) of the Constitution provides “On receipt of the report of a commission of Inquiry the President shall within six months publish the report and his or her comments on the report, together with a statement of any action taken, or the reason for not taking any action, thereon.”

Justice Njie said the White Paper is akin to a Government Notice published to satisfy the requirement of section 203 of the Constitution. He said the description fits the definition of a government notice in the Interpretation Act which states “A government Notice means any public announcement not of a legislative character made of a command of the President or by a Minister or public officer.”

He said a White Paper published pursuant to a Commission’s report does not make the latter capable of being executed. Justice Njie opined that the reference in section 203 of the Constitution to actions that may be taken by the President means actions that the Executive branch of government is legally able to make as empowered by the Constitution or other laws.

“It certainly, does not mean the exercise of judicial or quasi-judicial powers by the Executive in the form of pronouncement of White Paper,” the Judge held.

He said if, following the publication of a report of the Commission of Inquiry together with any adverse findings and or recommendations, the Executive intends to have imposed any penalty to any person adversely mentioned, the Executive must take the requisite court action, whether civil or criminal, in order to have those penalties imposed.

“I say this because since the Commission’s report, with or without a White Paper, cannot be enforced or executed as would be the case of a judgment or court order,” he said.

He added: “If the intention was for a Commission of Inquiry to have the power to impose criminal penalty or to grant civil remedies which could be executed or enforced, then in my view, that would have been clearly spelt out in the Constitution or the Act.”

Justice Njie said the 1997 Constitution and other laws of The Gambia do not provide for the suffering of liabilities by persons against adverse findings are made by the Commission of Inquiry.

“Therefore, after such findings are made, the Attorney General would have to take the appropriate legal steps, through the law courts, to ensure that such liabilities are suffered by those persons,” he said.

M.A Kharafi was represented by Counsel Combeh Gaye, while A. Ceesay and M.B Sowe appeared for the Attorney General.