By Yankuba Jallow with New Narratives

For decades faith in The Gambia was weaponised — not as a source of healing, but as a tool of political control. Under Yahya Jammeh’s authoritarian rule, mosques and churches became less places of worship and more instruments of state propaganda. Jammeh compelled Gambians to follow his religious directives or face arrest and prosecution.

Islamic leaders, seeking to appease the president, publicly praised him. Some bestowed titles like “Sheikh” and “Nasiru Deen” upon him and sought to justify his actions by comparing him to Prophet Yahya (John the Baptist in the Bible). Some Christian leaders did the same.

Now, years after the country’s Truth Commission concluded its work, religious leaders find themselves at a crossroads: How do you preach reconciliation in a land where religion has lost its credibility?

Leaders of both faiths say they have a lot of work to do.

“I think religious leaders should maintain their integrity and stay away from anything that compromises them,” says Francis Soska Forbes, pastor who runs his own church and has preached across the country for 29 years, often appearing on national television. “We should not chip in because of food, cars, and all that.”

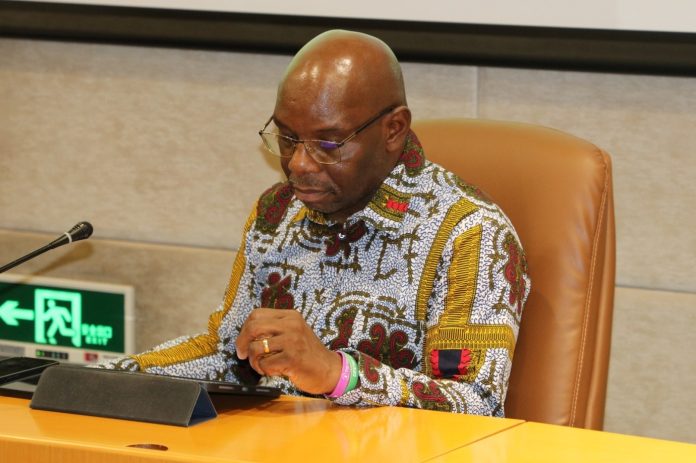

Imam Basirou Drammeh, a prominent figure in the Supreme Islamic Council and its representative in the Kanifing Municipality, agrees. “To be effective and credible as an Islamic scholar, you cannot be too close to power and you cannot be too far from power. That is our principle. That is our modus operandi.”

Experts say religious leaders have a long way to go to win back supporters. For 22 years, say experts, Jammeh blurred the lines between faith and state, declaring the country an Islamic Republic in 2015 and embedding religious control into public institutions. The consequences were both symbolic and concrete. Arabic inscriptions appeared in public spaces like schools and hospitals. Religious gatherings at the presidency became annual shows of loyalty. Silence became currency.

Pastor Forbes recalls the marginalisation of Christians that followed, dividing people who were previously united: “I, for one, have three aunties who married Muslims. I have first cousins who are Muslims. But Jammeh destroyed the social fabric of society.”

Jammeh bent many religious leaders to his will. The Christian Council of The Gambia routinely offered words of thanks at state functions. At the 2014 July 22nd Anniversary Celebrations, for example, representatives praised Jammeh for including Christian voices on national platforms. One said, “We are grateful for the opportunity to celebrate alongside our Muslim brothers and sisters under a government that respects all faiths.”

Bishop Solomon Tilewa Johnson, Anglican Bishop of Gambia (1990–2014), used his December 2011 Christmas message to praise Jammeh’s decision to declare Christmas a public holiday. Reverend Pierre Gomez of the Methodist Church, in public remarks during national celebrations and official functions, sometimes thanked Jammeh for fostering an environment where Christians could freely worship. At the 2007 Interfaith Forum in Banjul, Catholic Bishop Emeritus Michael Joseph Cleary, thanked the president for promoting national unity and protecting minority religions.

Forbes says he resisted Jammeh’s pressure, making him a target.

“Every Christmas, the former president gave money, alcoholic wine and turkey to churches,” recalls Forbes. He refused it. “A church member’s mother once called me and said I better be careful because ‘I have been told you don’t take the turkey.’ I said, ‘Yes, ma’am. But if I want to buy the turkey, I will go to the supermarket.’”

Islamic leaders also suffered because of Jammeh’s interference.

“He destroyed Gambian culture and relationships so he could reshape them to help solidify his power base—and he succeeded,” says Drammeh. “I don’t know about the Christian ones, but for the Islamic ones, he destroyed their credibility, respect, and relevance. He corrupted many and reduced them to pawns.”

“President Jawara was very, very careful not to mix Islam with politics throughout his presidency,” says Drammeh of Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara, Gambia’s first president. “Jammeh was the first to build a giant mosque at the presidential palace. That was the beginning of using Islam as a tool for political control.”

Kerr Mot Hali and the Burden of Unresolved Wrongs

Nowhere are the consequences of religious politics more visible than in Kerr Mot Hali, where an entire community was violently displaced in 2009. Followers of late Sering Ndigal, they were chased from their homes by paramilitary officers under Jammeh’s orders and forced into exile in Senegal.

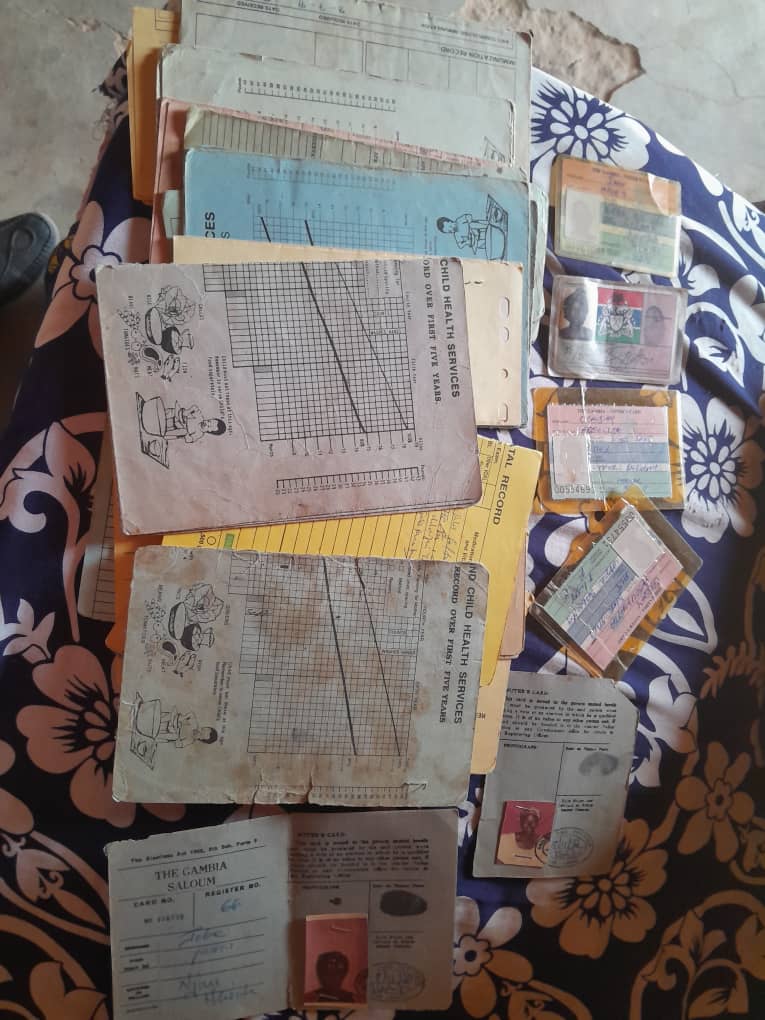

They have since obtained two High Court judgements affirming their right to return and reclaim their land and properties. The Truth Commission recommended the same, and the government accepted the recommendation. Kerr Mot Hali, a Gambian border community in Upper Saloum, remains stuck between legal victory and political inaction. The community’s predominantly Ndigal residents are still denied their return.

“The chief of that particular district is saying the issue of Kerr Mot Hali is a ticking time bomb and wherever a bomb explodes, we don’t know where it is going to stop.”, says Malim Ceesay, a program associate with the Women’s Association for Victim Empowerment.

Mariama Singhateh, senior counsel at the Ministry of Justice, acknowledged the difficulty: “This is not just about religion—it’s about society, identity, and citizenship. Most of them don’t even have basic documents.” She said the government is working on social cohesion initiatives that include all affected stakeholders to resolve the situation.

The damage of the past lives on in subtle but painful ways. Forbes described Christian grievances—particularly around sacred days and death.

“Good Friday is a public holiday in The Gambia. But on that day, sometimes, you see TV programs mocking Christianity,” he says. “I’m not telling you something hypothetical. I’m telling you what you know.”

He also cited burial discrimination: “If someone converts to Christianity and dies, the community may say he can’t be buried there. If buried, they exhume him. They don’t see the corpse as Gambian.”

“Little cracks in the wall always tell you something’s wrong with the foundation. If you don’t fix it, it will collapse.”

Both Imam Drammeh and Christian clergy now seek to rebuild trust.

“Now, the Supreme Islamic Council is no longer part of the government,” Drammeh says. “We’ve regained a bit of distance. Now we can make people talk again. And whenever our services are needed, we will deliver.”

The pair warns religious leaders to be vigilant should the same forces rise again. “Anything that looks like leadership trying to compromise us, we should resist. And we should speak.”

“Never Again” Is Not a Slogan

Experts say the Truth Commission’s work is done. The White Paper is published. Yet the real work is still ahead.

“Never again is a mantra,” says Forbes. “We all say it. People have to spend millions to possibly solve the problem. But if the problem is here and you’re not solving it here, you can write all your reports, and the next morning, you have a bigger problem.”

This story was a collaboration with New Narratives as part of the West Africa Justice Reporting Project.