MUHAMMED S. BAH (MS)

The extractive industry in The Gambia has been operating for decades, but experts and anti-corruption advocates believe it’s less transparent.

In 2017, the mining and quarrying sub-sector grew by 5.7% after contracting 10.3% the previous year, according to the 2018 African Economic Outlook.

The ministry of finance disclosed that from January 2020 to August 2020 over D511 million royalties was collected from fuel importation license.

From January to June 2020, the royalties generated from mining is about D23 million and in September 2020, government officials responsible for the extractive industry disclosed that the royalties on mining is about D30 million.

In the 2019 approved budget, it’s stated that the extractive industry generated over D78 million in royalties. In 2020 it is estimated that the royalties to be generated from the sector will increase by 47 million dalasi to D125 million.,

The government’s openness in reporting on monies generated from the extractive industry was considered short by financial transparency activists after nothing was reported on the revenue gained from royalties in 2018.

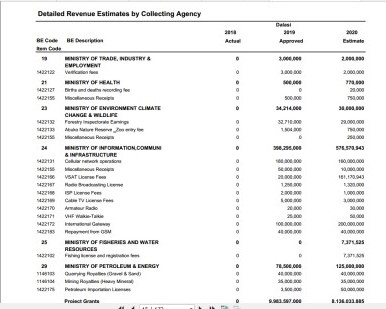

Detailed revenue estimate by collecting Agency in the 2020 approved budget

It has been reported that the Gambia’s natural resources have for decades been a source of power and wealth for the nation’s ruling elites, and less often for Gambians themselves.

The competition for control of revenues from extractive industries has fuelled series of corruption, conflict within various communities and has left those communities to wallow in poverty, restricting them opportunities and social development.

According to Marr Nyang, the Executive Director of ‘Gambia Participates,’ an anti-corruption organisation in the Gambia, “if these resources are used effectively, the country will harness more development and poverty will be eradicated.”

Mr. Nyang said the information provided from the extractive and non-extractive industries for public consumption is scanty and unorganised. He added that “there is no organised database or system that can identify where the country has extractive and non-extractive [resources].”

He said this is something that is of importance and should be considered by the government. He said both the extractive and non-extractive industries provides a lot of revenue which he thinks the government is not aware of or is under-reporting.

Mr. Nyang cited the recent Environmental Investigation Agency’s (EIA) three-year

investigation into the Senegal-Gambia-China rosewood trafficking that uncovered unprecedented evidence on a series of major forest crimes.

“The EIA report indicates that an estimated 1.6 million trees have been illegally harvested in Senegal and smuggled into The Gambia between June 2012 and April 2020,” he said. Nyang also said that the unaccounted export volume and potential revenue loss in the Gambian timber sector are considerable, with The Gambia reporting US$471 million less in exports than its trading partners declared as imports between 2010 and 2018. The EIA report, he said, mentioned top government officials who benefitted from this trade at the expense of the masses.

He cited that there are a lot of activities ongoing on the country’s natural resources but little or no determination has been made by the government as to how much is generated from this sector.

In 2009, reports emerged that Gambia’s extractive industry is least transparent. The Gambia Journal specifically pointed some of the expert’s opinions on the industry more especially on the Carnegie Minerals. The government had suddenly announced that it was giving the mining company Carnegie Minerals Gambia Ltd a week’s ultimatum to come out clean on the types of minerals it was mining and shipping out of the country.

In June 2020, an investigative article published on Malagen revealed the sector was least transparent. The investigation found out that GACH Company LTD reveals that in three years of its operations. The company exported more than sixteen thousand tons of heavy mineral sand, generating a conservative revenue estimate of US$2.4 million (approx. D124.9 million). Out of that, only US$293 thousand (D15.1 million) – less than 13 percent of the revenue – has been paid to the government as royalties.

Anti-corruption campaigners and other economic activists believe the transparency in the industry is far from realistic.

Marr Nyang said there is no much information in the national budget on extractive and no extractive, and most of the revenue you see on the national budget is on tax and non-tax activities. The only thing I have seen so far is that of the oil royalties from the ministry of petroleum, which is about D500 million.

He cited the EIA report on how the country under-reported the $471 million in the rosewood dealings. Probably the government lacks the seriousness to take care of the extractive industry because few individuals might be benefiting at the expense of the public.

Government to improve accountability in the extractive industry

Nyang call on the Geology Department to work towards having a database on their website regarding all the mining sites and categorizes the extractive and non-extractive of this country. He added that the information published on the site should give an estimated revenue of that is collected from these sites.

“If they can do that, they will tell the public how much is generated from each mining site and how much is generated from the extractive and non-extractive industries per annum,” he underscored.

He said there is a need for people to know who are those in the mining sector and how are licenses given to them. “We have seen vessels given license and they are going beyond their license and also those in the forestry gave licenses to people and they go beyond what they are given.” He remarked. He said Government should constitute a special law enforcement agency to ensure that they enforce the regulations in the extractive industry.

Marr suggested that government should constitute a body to monitor the natural resources, its impact, and the income it generates. “The integral body will also look at the impact assessment of the exploration of these resources both the long-term short-term impacts.” He added that they can also suggest policies that will encourage mining in line with environmental sustainability.

Marr Nyang, Executive Director of ‘Gambia Participate’

Lamin Dampha, an economist and a lecturer at the University of the Gambia, said even during Jammeh’s regime mineral sand is been exported to China, without much been known to the public.

“The Mines and Quarrying act 2005 have vested the state ownership of all mining sites.” Dampha said. He however said it’s important for the government to consider those communities where the sites are located, to be given responsibilities, and also put in the picture as to how much revenue is been generated from these sites. He cited the Faraba Banta incident, where communities questioned the transparency aspect of the ongoing mining. He said this brought about a problem that claims the lives of people within the community, he added: “Given the fact that few people were benefiting from the mining sites at the detriment of the masses.”

Mr. Dampha, who is also a researcher, said the Gambia is never short of good laws, the laws that clearly spelled out what is expected of government. He said the Mines and Quarrying Act 2005 and the Petroleum Act 2004, all clearly articulate the duty of government in regulating the extractive industry.

He suggested that the Government should do more of policing to ensure the laws are implemented to the latter. He added that the “government should ensure companies involved are closely monitored and also keep track of their activities.”

In the accountability process, Mr. Dampha believes that the Government should make the best use of online platforms, to put all relevant information without sheltering the information. He calls on the authorities to be more open, adding ministries and departments responsible in the extractive industries should be having public briefings to tell the people what they are doing, and how much is generated. “Through this way, people can ask questions and seek clarification.”

Government’s Efforts in the industry:

Officials in the extractive industry disclose that the government is working towards strengthening access to information on the extractive industry. The Ministry of Petroleum is working on a website which will be launched very soon, before the end of 2020 as disclosed by officials under the ministry.

This website as stated by officials will be up and running, and it will also entail details of what is generated from the extractive industry. “In the website, data of all the resources extracted annually will be featured”, as disclosed by Government officials, this is expected to help people to know what is accrued to the government as royalties from each extraction.

There are two types of extraction, one of which is called development minerals. Government’s objective is to stimulate the sector because it is a chain, which includes the miners, the truckers, the middlemen the consumers, and the value-added chain is within the Gambia and nothing is export.

Therefore, the Government put emphasis more on stimulating the sector, than putting the emphasis more on the royalty revenue collected, notwithstanding officials noted that all royalty collected are deposited to the central bank through the treasury. The economic impact is huge even the government didn’t collect royalties. An official under the Geology department cited that over 400 trucks are involved in the mining, and for example each can make D10,000 minimum per day, other Gambian cement companies will benefit and enterprises that sell building materials as well. In 2019 the Government gets D39 to D40 million on just royalties paid on quarrying (sand and gravel) only.

According to the official the heavy mineral sand or valuable minerals or exported resources, there is no continuity in the operation. It can be produced, in a month and put to stop, for example, the whole of 2020 they have not been producing in the best part of the year, very little is happening, what was paid in 2019 in US Dollars was about $350,000.