By Nelson Manneh

As dawn breaks over the coastal city of Kanifing, a small crowd begins to gather outside the national ID card processing center, many of them having risen before sunrise to secure a spot in line. By 6 a.m., the queue is already forming — hopeful applicants clutch documents, fan themselves under the rising heat, and brace for what has become a tedious rite of passage for thousands of Gambians seeking a basic, yet vital, credential: the national ID card.

But on a recent Tuesday and Wednesday, what awaited them was not a swift application process but locked doors and dead screens — the result of a power outage that paralyzed one of the country’s busiest ID issuance centers.

“I left my house in Dippa Kunda around 5 a.m. and was here before 6,” said Naffie Jarju, a visibly exhausted applicant. “We waited and waited. Eventually, someone told us there was no electricity. But the next building had power. That’s what confused me.”

The problem, several applicants said, wasn’t an isolated blackout. According to one individual who requested anonymity, the Kanifing center’s electricity had been cut due to unpaid bills. “I overheard staff saying they hadn’t switched to cash power and were still relying on NAWEC bills,” the applicant told this reporter. “That’s why they were disconnected.”

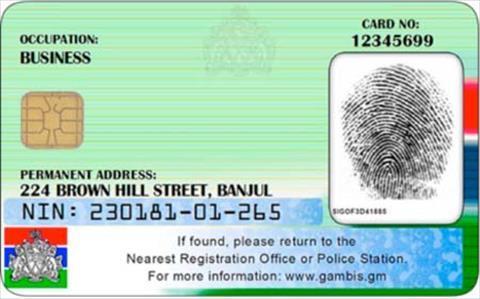

The Gambia’s national ID card — a biometric identification document issued by the Immigration Department under the Ministry of Interior — is legally required for all citizens over 18. The process to obtain one is supposed to be straightforward: submit documents such as a birth certificate or passport, get fingerprinted, pay a fee, and wait for the card to be processed. In reality, it has become a drawn-out and frustrating ordeal.

Applicants must not only endure long lines and poor service but also contend with technical failures, inconsistent information, and in some cases, complete shutdowns of the centers.

“It feels like applying for a visa to a foreign country,” said Jarju. “Except it’s my own country and my own ID.”

The Gambian Constitution does not explicitly lay out the framework for national identification cards, but laws mandate their possession. Failure to produce one when asked can result in fines or even arrest. For many, especially those working in the informal sector or traveling between regions, having the card is essential.

“I have all my documents,” said Victor Mendy, another applicant who spent two days at the center. “I followed the process, did everything they asked, and yet I’m still here waiting. It’s not wrong to have procedures. But it’s wrong to suffer while following them.”

Since 2009, Gambia’s ID card system has been biometric, first managed by Innovatrics and then, from 2018, by the Belgian company Semlex. The cards cost 450 dalasi — a significant sum for many — but the real price, applicants say, is measured in time, lost income, and mounting frustration.

Mariama Ngum, a street vendor, said she had come multiple times but still hadn’t made progress. “The Tobaski holiday slowed things down, they said. Then I came again early Tuesday, only to find no electricity and a broken generator. This is a government facility — how can they not have a backup plan?”

For now, applicants like Ngum, Mendy, and Jarju wait — some under the shaded corners of the building, others pacing in frustration, still others praying the power returns before closing time.

The Immigration Department says it cannot shoulder the blame. “ID card issuance falls under the Ministry of Interior,” said Inspector Siman Low, the department’s spokesperson. “All operational expenses, including electricity and logistics, are managed by the ministry. If there are disruptions, the ministry would be in the best position to explain.”

Officials from the Ministry of Interior did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

For many Gambians, the wait for an ID card is not just a bureaucratic inconvenience but a painful symbol of how even the simplest rights can become elusive. In a country where identification opens doors to jobs, services, and legal protections, being without one can mean being invisible.

Back in Kanifing, as the sun rises higher and the heat intensifies, the line outside the center grows longer. So does the list of frustrations. “We’re not asking for charity,” Jarju said. “We’re asking for our rights.”