By Lamin Fatty

A high court judge in Banjul has made orders barring anyone from interfering with the construction of a mosque and Arabic school by so-called ‘slaves’ in Garawol.

The Court said they have the right to construct their mosque and Arabic school without any hindrance from the so-called noble class.

The court ordered that the Chief of Kantora, the Alkalo of Garawol and all residents of Garawol should stop discriminating against the people being referred to as slaves.

The case was instituted by Gambanaaxu (applicants) on behalf of the so-called slave class of Garawol. They sued the Governor of the Upper River Region, the Chief of Kantora District and the Alkalo of Garawol seeking several court declarations.

Justice Aminata Saho-Ceesay declared that the naming, labelling, calling the Applicants’ Slaves’ or ascribing any title to them connoting an inferior social status in order to discriminate against them is a gross violation of their fundamental rights to equality before the law. She further declared the naming, labelling or calling the applicants as “Slaves” is unlawful, illegal, and unconstitutional and such culture, tradition or practice is hereby declared unlawful and unconstitutional.

The Judge delivered a judgment in favour of the so-called slave class saying they have the constitutional right to their practice and manifest their right freely. The court made orders prohibiting anyone from trying to interfere with the construction of a mosque and the Arabic school they intend to build in Garawol. She held that the interference with the fundamental rights of the so-called slave class to practice their religion freely was in violation of their constitutional right to practice the same freely.

The application invoked the exclusive original jurisdiction of the high court seeking enforcement of their fundamental rights.

They asked the court to make an order prohibiting the Respondents (Governor of URR, Chief of Kantora and the Alikalo Garawol) from interfering in any way with their fundamental rights to freely practice their religion by constructing a mosque and an Arabic Islamic school without any interference in any way whatsoever. Secondly, they wanted the court to make an order that any interference with their fundamental rights to freely practice their religion amounts to a violation of their Constitutional right to freely practice their religion. Thirdly, they asked the court to make an order that naming, labelling, and calling them ‘Slaves’ is a gross violation of their fundamental rights to equality before the law. Fourthly, they asked the court to make an order that any further calling and naming of them as ‘Slaves’ is unlawful, illegal and unconstitutional and such culture, tradition or practice to be declared unlawful and unconstitutional.

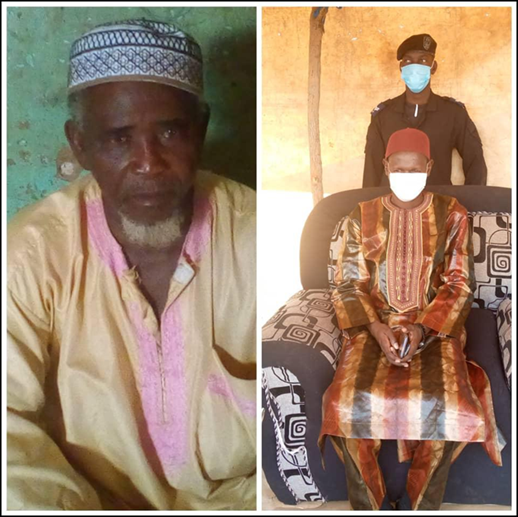

Alagie Modi Trawally was the patriarch for Gambanaxuu. The Respondents were the Governor of URR (Samba Bah), the Chief of Kantora District (Alh. Bacho Ceesay) and the Alkalo of Garawol Village Tachineh Ceesay. The applicants claimed that the Chief and the Alkalo are the heads of a group of families known as the ‘Nobles’.

It was their case that they suffered discrimination at social events such as funerals, weddings and christening ceremonies and, more importantly, that their constitutional right to practice their religion freely is being infringed. They claimed that they are denied from praying inside the Garawol central mosque. This was how they began performing their daily and congregational prayers in a compound because they were forbidden to pray at the central mosque. One Alagie Marie Keita offered them a piece of land to build a mosque and a school. It was their case that they were at times excluded from attending funerals and other ceremonies. It was their claim that they were barred from participating in communal development when they began making demands for equality. It was their case that they were denied usage or access to the cemetery.

In 2014, according to their claims, they went to the Alkalo demanding an end to the discrimination they were facing. The Akalo told them they had two options – either to vacate the village or accept the name “slave” because their ancestors were slaves.

They informed the court that Alkalo, the Chief and the Governor did not allow them to build their school and mosque.

The court held that the statements contained in the statement of the case by the so-called slave class were true since there was a concession to the case.

The Judge cited Section 25(1) (c) of the Constitution of The Republic of The Gambia, 1997 which bestows every person with the fundamental right and freedom to practice religion and manifest such practice. Section 32 of the Constitution also provides unequivocally that every person shall be entitled to enjoy, practice, profess, maintain, and promote any culture, language, tradition, or religion.

Articles 2, 3, and 8 of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights, uniformly prohibit discrimination, guarantees equality and equal protection before the law, freedom of conscience, and the free practice of religion. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights also proclaims that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. It further prescribes that everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set out therein, without distinction of any kind, particularly regarding race, colour or national origin.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights further provides that all human beings are equal before the law and are entitled to equal protection of the law against any discrimination and any incitement to discrimination.