By Yankuba Jallow with New Narratives

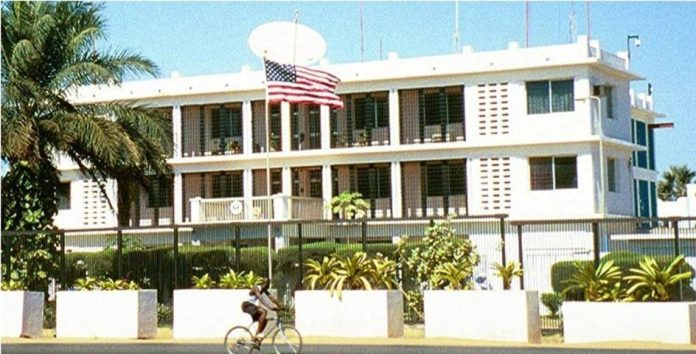

The United States government is reportedly considering shutting down its embassy in The Gambia, an unprecedented diplomatic retreat that would mark the first closure of an American mission in Banjul since it was established shortly after the country’s independence in 1965.

According to a leaked internal memo from the U.S. State Department, obtained and reported by The New York Times on April 15, the Trump administration is weighing a broad restructuring of American diplomatic missions worldwide. The plan outlines proposals to close 10 embassies and 17 consulates, with staff reductions or consolidations in dozens of others. Though undated, the memo appears to be an expansion of earlier discussions within the Trump administration to cut State Department operations by as much as 50 percent—a reflection of the president’s push to slash foreign aid and reduce U.S. global engagement.

Among the six African countries where embassies have been proposed for closure is The Gambia, alongside the Central African Republic, Eritrea, Lesotho, the Republic of Congo, and South Sudan. The memo reportedly suggests that the functions of these missions be transferred to larger, regional embassies in neighboring countries—a move that would effectively eliminate Washington’s direct diplomatic footprint in Banjul.

In The Gambia, where U.S. engagement has long underpinned development, democracy, and civil society efforts, the mere suggestion of closure has stirred alarm and disbelief.

“It’s not just a building that may be closing—it’s a whole era of partnership that could end,” said Muhammed Lenn, a political science lecturer at the University of Civil Service, formerly the Management Development Institute. “The embassy’s presence goes beyond diplomacy. It is central to development, education, and governance reform in this country.”

The U.S. Embassy in Banjul was established in September or October 1965, shortly after The Gambia secured independence from British colonial rule. Since then, the embassy has served as the conduit for a wide range of American assistance programs, from technical support to government ministries to direct funding for civil society organizations, media, and human rights initiatives.

Lenn noted that the embassy has played a pivotal role in helping Gambian institutions access U.S. government funding, citing the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) as a prime example. Although the MCC compact for The Gambia has been frozen in recent years due to governance concerns, Lenn emphasized that the embassy had facilitated the preparation and application process for a $25 million program to support The Gambia’s struggling national utility company, NAWEC.

“The support was meant to stabilize the supply of water and electricity—two of the most basic and urgent needs of the Gambian people,” he said. “To lose access to that kind of aid is devastating.”

Equally critical, he said, is the potential disruption to U.S.-Gambia exchange programs that have enabled students, academics, civil servants, and young leaders to study and train in the United States under prestigious initiatives such as the Mandela Washington Fellowship. “Those programs are not just educational—they are transformative,” Lenn said. “They shape the future of our leadership.”

Trade and economic relations may also be impacted. The Gambia has been a beneficiary of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a U.S. trade program that allows duty-free access to American markets for qualifying African countries. Though modest in scale, AGOA has supported small-scale Gambian exporters in agriculture and textiles.

“If the embassy closes, how will these economic partnerships be sustained? Who will oversee compliance and provide support?” Lenn asked. “All these opportunities might be lost.”

Practical consequences of an embassy shutdown would likely be felt immediately by ordinary Gambians. For thousands of visa applicants each year—students, businesspeople, tourists, and immigrants—the closure would mean travelling to Dakar, Senegal, for interviews and biometric processing. “It’s not just a matter of inconvenience,” Lenn said. “It’s an economic burden. For many Gambians, the cost of travel, accommodation, and application fees is prohibitive.”

Responding to questions, Andrew Posner, Public Affairs Officer at the U.S. Embassy in Banjul, said that no closures have been announced and that the embassy remains operational. “The State Department continues to assess our global programs and posture to ensure we are best positioned to address modern challenges on behalf of the American people,” he wrote.

Still, speculation intensified earlier this month when the embassy published an announcement on its Facebook page stating that it would host a public auction of office furniture, vehicles, IT equipment, and other assets. Scheduled for April 26 at the embassy’s warehouse in the Kanifing Industrial Estate, the sale prompted concern that the embassy was liquidating its assets in preparation for closure. The viewing and auction were abruptly postponed a week later, with no explanation given beyond a brief social media update.

“Public Auction Postponed,” read the April 25 post. “Please check back here in the future for announcements about a rescheduled auction date.”

The lack of clarity has left civil society leaders and government officials grasping for answers.

“It’s very unusual for an embassy to auction off core equipment and vehicles unless they’re scaling back or leaving,” said a senior official at a Gambian non-governmental organization that has worked closely with the embassy on democracy initiatives. “Whether this is part of a broader plan or not, the uncertainty is already damaging.”

The possible closure comes at a sensitive time for U.S.-Gambia relations. Since the end of Yahya Jammeh’s 22-year autocratic rule in 2017, The Gambia has embarked on a fragile transition toward democratic governance and transitional justice. The U.S. has played a prominent role in supporting that process, funding civil society groups, backing the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission, and facilitating reforms in security and justice sectors.

That support has not gone unnoticed by Gambians, many of whom see the U.S. as a key ally in the fight against corruption, impunity, and underdevelopment.

“If the U.S. pulls out now, it sends a troubling signal to both the government and the people,” Lenn said. “It could be interpreted as abandonment. And that would have consequences far beyond the loss of an embassy—it could affect how other partners view The Gambia’s viability as a democratic project.”

As of now, the embassy gates remain open, the flag still flies, and official statements maintain a posture of continuity. But the prospect of losing one of the country’s oldest and most influential diplomatic missions has cast a long shadow over Banjul’s diplomatic and political landscape.

“It would be more than a closure,” Lenn said. “It would be the symbolic end of a historic relationship.”

This story was a collaboration with New Narratives as part of the West Africa Justice Reporting Project.